The recent release of the 2024 Pew Center Research’s Religious Landscape Study (RLS) offers a goldmine of information for scholars of American religion, because it provides the best dataset we currently have for understanding the past, present, and potential future of American Christianity and other religious groups.

The initial headlines about the new RLS focused mainly on the number of “nones” – which, as you probably saw, are far more numerous than they were in 2007 or 2014 (the years of the first two Pew RLS’s), but not significantly more numerous than they were in 2021, a trend that may indicate a slowing rate of religious disaffiliation than some pundits had predicted five years ago. I’ll say more about that in a future post.

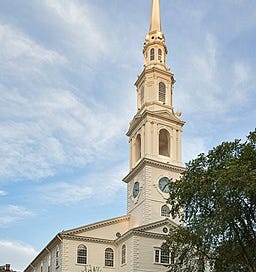

For the next few posts, though, I will focus on other parts of the RLS that didn’t attract quite as much attention in the initial headlines when the survey was released last week. Today’s post will focus on the group that in the mid-twentieth century was the largest and most influential group of American Christians, but which today is one of the smallest and most beleaguered: mainline Protestants – that is, the liberal (or ecumenical) Protestant denominations that include the United Methodist Church, Episcopal Church, Evangelical Lutheran Church, Presbyterian Church (USA), American Baptist Churches USA, United Church of Christ, and Disciples of Christ, along with a handful of other similar denominations.

Mainline Protestantism has been declining in numbers since the late 1960s, but the last seventeen years have seen an especially precipitous drop in the number of mainliners. In 2007, mainline Protestants comprised 18 percent of the American population. By 2024, they made up only 11 percent. No other Christian group experienced such a drastic numerical decline during this period.

This naturally leads to two questions: What caused this decline? And what is the future of the mainline, now that this decline has occurred?

On one level, the decline of mainline Protestantism is easy to explain through demographics: Mainline Protestant denominations were not able to retain their young people in the late 1960s, and since then, they have continued to lose their younger adults at a greater rate than other American Christian groups. As a result, mainline Protestants are now the oldest group of American Christians, with a median age of 59. Thirty-eight percent are retired. They’re also a more heavily female group than any other group of American Christians; 59 percent are women. And they’re more white, more educated, and more affluent than any other Christian group, even if they have become a little more multiracial in the last fifteen years. The stereotype of mainline Protestant congregations consisting mainly of elderly church ladies who are busy with congregational committee work is largely true.

But all of this begs the question of what caused mainline Protestant denominations to lose their young people or bring in new converts. While the RLS cannot provide conclusive answers to this question, I can suggest a few:

1) Mainline Protestant church attendance rates were significantly lower than evangelical or Catholic church attendance rates even in the early 1950s. As a result, while large numbers of Americans claimed a mainline Protestant affiliation, their commitment to their local church may not have been particularly strong, especially in the eyes of their kids. When the kids grew up, perhaps it’s not surprising that church wasn’t all that important to some of them.

2) Mainline Protestant denominations are too moderate for progressives and too liberal for conservatives, and they are plagued by significant political disagreements between clergy and laity. While mainline Protestant lay members generally hold moderate, centrist views on politics and religion, with a wide tolerance for pluralism, but mainline Protestant denominations and clergy tend to lean heavily toward progressive politics. A 2023 PRRI survey showed that while Democrats outnumber Republicans among mainline Protestant clergy by nearly 4 to 1, Republicans outnumber Democrats among mainline Protestant laity. There is thus a significant disjuncture between the stated ideological leanings of mainline Protestant denominations or clergy (who tend to hold positions that reflect the progressive political stances of the denomination) and members, who tend to be much more politically centrist.

With such a wide disjuncture between what the clergy believe and what the typical mainline Protestant member thinks, it should not come as a shock that some mainline Protestant kids grow up wondering why they needed to bother with church at all. Those who are more liberal may wonder why they need church at all, since they have quite likely noticed that the constraints of congregational life often prevent clergy from being as forthrightly politically progressive as they would like. And those who are more conservative (whether theologically or politically or both) may find it easy to write off mainline Protestant denominations that have taken liberal stances on abortion and LGBTQ+ issues. The result is an atrophy of members among both conservatives and liberals.

3) Mainline Protestant churches were so closely linked to other liberal democratic institutions in the United States, including colleges and political advocacy organizations, that these institutions largely replaced the church as a forum for the type of social advocacy that the institutional church once played a central role in providing. For younger mainline Protestants, the distinction between, say, a college program in the humanities and a mainline Protestant church or a career in political advocacy and membership in a progressive congregation was now so nebulous that church seemed superfluous. This is why David Hollinger argues in Christianity’s American Fate that mainline Protestants have succeed in winning the American culture even as their ecclesiastical institutions have declined almost to the point of oblivion. American colleges are essentially the product of mainline Protestant values. So is the Democratic Party. So is part of the American media. But now that mainline Protestantism has diffused itself into generic liberal democratic American culture, mainline Protestant ecclesiastical institutions be necessary. At least, that’s one way of looking at the matter.

All of these trends have been operating for more than half a century, but in the last fifteen years, there has been another reason for mainline Protestant membership decline: the fragmentation of most of the major mainline Protestant denominations over LGBTQ+ issues and related matters. In the last decade and a half, mainline Lutheran, Episcopal, Presbyterian, and Methodist denominations have split, with significant numbers of conservative members leaving the mainline to form new evangelical-aligned denominations that take conservative positions on abortion and homosexuality.

Mainline Protestant denominations are now a little more homogeneously progressive than they were a decade or two ago, but they’re also significantly smaller.

So, what does the future hold for mainline Protestantism?

I think that there are at least three possibilities:

Possibility 1: Mainline Protestantism will continue to shrink as the already disproportionately elderly memberships continues to age. More congregations will fold. More denominational agencies will shrink. More seminaries will close or merge. And the political influence of mainline Protestantism will continue to wane. This, in fact, is probably the most likely scenario, because it merely extrapolates from trends that are already well underway. And if this happens, American democratic institutions that were based on mainline Protestant values will probably also suffer, as indeed they already have.

Possibility 2: Mainline Protestant denominations will become a newly revitalized, more homogeneously progressive coalition that will remain small but become increasingly influential as a liberal force in American public life. Now that many of the conservatives and moderates have left the mainline to form new denominations during the recent church splits, mainline Protestants are more homogeneously progressive. And they are arguably more energized. At a time when the national political culture has shifted sharply away from the liberal democratic values that mainline Protestants have promoted for decades, mainline Protestants may have strong motivation to fight against these trends, just as conservative evangelicals were motivated in the late 1970s to take back their country by bringing their own values into politics. In other words, we may be poised to see a newly revitalized Religious Left, with mainline Protestant churches leading the way in a religiously ecumenical coalition.

Possibility 3: Mainline Protestant churches will reclaim their voice as forces of tolerant political moderation. This, I suspect, is the least likely possibility, but if it happens, it would probably be good for American democracy. For the past half century, mainline Protestant churches have been a model of political pluralism and tolerance, with clergy that leaned to the political left and a membership that was more conservative. Denominations often found a way to steer a center-left course in both theology and politics, with political stances that melded calls for social justice with references to the historic Christian tradition.

Mainline Protestant theology may have left much to be desired, but if mainline Protestantism continues to erode as a meaningful cultural and political force in American life, the effects of its disappearance will have catastrophic effects on institutions that extend far beyond church walls or denominational boundaries. But a full analysis of that larger cultural and political phenomenon will have to wait for a future post.