The Southern Baptists who met for their denomination’s annual convention last week passed a bevy of resolutions on a number of hot-button cultural issues, but one traditional Southern Baptist concern was conspicuously absent from the resolutions – alcohol.

Even though this was the year when the US surgeon general issued a new warning saying that alcohol has been conclusively linked to seven types of cancer and that even very moderate drinking can have negative health effects – and even though secular media outlets have published numerous articles about the latest findings of alcohol’s dangers – Southern Baptists did not comment on the issue at their convention.

A silence on alcohol at a time when the medical establishment and the mainstream media are publicizing its dangers would have once been inconceivable for the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC). After all, the SBC passed an anti-alcohol resolution at every annual meeting between 1968 and 1976. And during the 1980s, the denomination passed anti-alcohol resolutions at seven of its ten annual conventions.

But the SBC has not passed a resolution on alcohol since 2006. Although its endorsement of total abstinence from alcohol still remains the denomination’s latest word on the subject, the SBC has clearly lost interest in what was once its signature political cause.

Many evangelical Christians might view this as a good thing. If the Bible includes references to wine as a blessing from God and does not mandate teetotalism, a church or denomination has no business categorically denouncing alcohol, they might argue. Other evangelicals who worry about rising rates of alcoholism among at least some groups of Christians might view the SBC’s loss of interest in fighting alcohol in more negative terms. But in this post, I’m more interested in finding out the historical explanation for this shift than in taking sides on whether it’s a good thing or a bad thing. After all, regardless of what we think about it, the demise of a campaign that lasted more than a century in America’s largest Protestant denomination is certainly a significant development, and it deserves a historical explanation.

So, what might explain the rapid decline of the anti-alcohol campaign in the Southern Baptist Convention during the past thirty years?

To answer that question, we need to look at what prompted this campaign to begin with, and then we can examine what happened to the campaign once the political and social situation changed.

The Origins of the SBC’s Campaign against Alcohol

Although the SBC was not the first denomination to embrace the temperance movement, its public campaign against alcohol may have been the longest-lasting of any Christian group in the United States. But when the denomination first publicly committed itself to the campaign against alcohol, its stance was not at all unusual or sectarian; it was simply following the lead of other Protestant denominations. And the primary focus of its early resolutions on the issue was not personal holiness or conformity to biblical standards; it was instead political action based on a particular social vision.

The SBC’s first anti-alcohol resolution, passed in 1886, said nothing about personal consumption of alcohol at all. Instead, it stated that since “the manufacture and sale of intoxicating liquors as a beverage” were “opposed to the best interests of society and government,” members of the SBC pledged to use their influence “socially, morally, religiously and in all other proper ways, to work for its speedy overthrow.” In other words, they were pledging their support for the Prohibitionist cause.

This was the way that several of the nation’s other leading Protestant denominations saw the alcohol issue at the time. Northern Presbyterians and Methodists had already embraced the temperance cause in the early nineteenth century, but in the 1880s, the South’s leading Protestant denominations followed the lead of their northern counterparts in pledging their support for the political cause of Prohibition. The Southern Methodist Church – which had long encouraged teetotalism among its members and especially its ministers – appointed a Committee on Temperance and Constitutional Prohibition in 1884. And in 1886, the General Assembly of the Southern Presbyterian Church (known as the Presbyterian Church in the United States) likewise adopted a Prohibitionist resolution.

“As the traffic in and use of intoxicating liquors as a beverage are the prolific causes of so much crime, poverty and suffering in our land, and as it costs the people so much money in criminal prosecutions and the support of the victims of drink, and as it is one of the greatest enemies of the Church of Christ in destroying the sanctity of the Christian Sabbath in its right observance wherever its blighting influence is felt, and as we are warned against its effects in 1 Cor. 6:10; therefore, in view of these terrible effects, this General Assembly bears its testimony against this evil, and recommends to all our people the use of all legitimate means for its banishment from the land,” the PCUS General Assembly proclaimed.

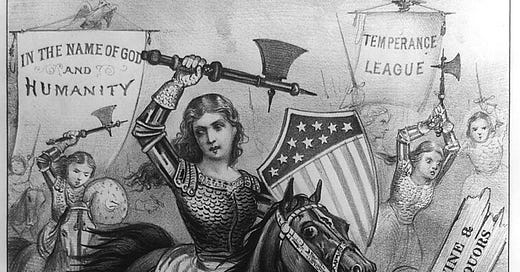

The Southern Baptist Convention’s initial endorsement of Prohibition was thus thoroughly in the southern Protestant mainstream. And it was based on an optimistic Protestant vision of social order and societal uplift that sought to protect the nuclear family, the interests of women, and public health. The PCUS General Assembly’s resolution was a direct response to the petitions of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, which was led at the time by the Methodist Frances Willard but that also had many Presbyterian members. I was not able to find out whether the SBC resolution of that same year was based directly on lobbying from the WCTU, as the Southern Presbyterian resolution was, but even if it was not, it likely attracted support for the same reasons.

The temperance (or anti-alcohol) cause received more Protestant denominational support than any other social cause of the late nineteenth century because it cut across all ideological and political divisions. It appealed to progressive women’s suffrage advocates like Willard, who viewed Prohibition as a way to protect women and the home, and it likewise appealed to conservative advocates of personal holiness who were willing to endorse Prohibitionist legislation even while eschewing other aspects of the Social Gospel. It appealed to African American women who viewed Prohibition as a path to racial uplift, as well as to white racists, who saw Prohibition as a way to control the African American population by limiting their access to liquor.

For all of these Protestants, the campaign against alcohol was a way to fight the power of the saloon. Alcohol consumption rates in the United States were higher in the early nineteenth century than they were in the 1880s or 1890s, but the number of saloons was much lower. By the end of the nineteenth century, there were more saloons than groceries or meat markets in the United States, and they were especially prevalent in ethnic neighborhoods in cities. New York City alone had 2,000 saloons in 1900. Many women considered these all-male enclaves dens of political and social corruption. They were commonly associated with Irish Catholics or German immigrants. The Protestants who joined the anti-alcohol campaign were especially eager to destroy the saloon, which is why one of the largest temperance organizations (second only to the WCTU) of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was called the Anti-Saloon League. It received most of its support from Protestants.

The SBC’s focus on anti-alcohol lobbying as its primary political concern was evident in the original name of the predecessor of the SBC’s Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission – the Committee on Temperance, founded in 1908. Only later did the purpose of this denominational agency broaden to include other social and political issues.

But if fighting alcohol was the SBC’s primary political concern in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there was nothing about its official stance at the time that set Southern Baptists apart from most other southern Protestants, as well as many Protestants north of the Mason-Dixon line. Southern Methodists were just as strongly opposed to alcohol (if not more so), and Southern Presbyterians were likewise opposed to the liquor traffic. But in the mid-twentieth century, that started to change; even as other Protestant denominations started to back away from their anti-alcohol stances, Southern Baptists doubled down on theirs.

The Decline of the Protestant Anti-Alcohol Campaign

Southern Methodists reconciled with Northern Methodists in 1939, and the new United Methodist Church rescinded its prohibition on pastors’ consumption of alcohol in 1968. Southern Presbyterians united with Northern Presbyterians in 1983, and the newly enlarged Presbyterian Church (USA) adopted a resolution that encouraged a cautious approach to alcohol while still allowing for its use in moderation.

By that time, the old-style saloon was now a distant memory, since Prohibition had killed it. And Prohibition itself had not been the success that Protestant temperance advocates had hoped for. Although it did succeed in destroying the saloon – and although it arguably led to a reduction in alcohol consumption rates – it also led to a widespread disrespect for the law that manifested itself in a new youth drinking culture that included women as well as men.

While many Protestants continued to frown on alcohol use throughout the mid-twentieth century, support for total abstinence gradually narrowed. Mainline Protestant denominations were the first to make peace with the moderate consumption of alcohol; by the 1950s, teetotalism increasingly marked one as an evangelical rather than a mainliner. And by the 1970s, an increasing number of evangelicals were openly imbibing, even though a number of evangelical denominations (and evangelical colleges) retained their official opposition to alcohol.

But for a while, among conservative southern evangelical Protestants, opposition to alcohol became a symbol of Christian identity and a form of resistance against alcohol’s acceptance in the larger culture. Southern Baptists were in the vanguard of this resistance.

In contrast to the southern Presbyterians and Methodists, Southern Baptists neither reconciled with their northern counterpart (the American Baptist Churches USA) nor moderated their stance on alcohol. Instead, they passed a bevy of anti-alcohol resolutions in the 1970s and 1980s that reaffirmed both the denomination’s commitment to total abstinence and pledged their support for the political fight against alcohol advertising.

It’s hard to say for sure what motivated all of these resolutions, but I think that the timing was likely not coincidental. Alcohol consumption rates were increasing in the 1970s, paralleling similar increases in illicit drug use, divorce, and public acceptance of sex outside marriage. By taking a strong stand against alcohol, Southern Baptists signaled their resistance to these cultural trends. And as the only major southern Protestant denomination that did not reunite with its northern counterpart, Southern Baptists took on the role of the lone cultural guardians of a southern Protestant moral tradition that included opposition to alcohol.

Southern Baptists grounded this opposition in a sociological or scientific claim. Alcohol consumption was a bad idea not because the Bible mandated it but because medical evidence and social science statistics indicated the destructive impact of alcohol’s use as a recreational beverage. This had been the approach of the temperance movement in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and it remained the SBC’s approach in the 1970s. Alcohol was a highly addictive drug, they argued; it was difficult to use safely in moderation, so the best course was to avoid it entirely.

At a time when the denomination’s leaders were polarized between a moderate faction that wanted to focus on civil rights and a conservative faction that wanted to give primacy to the pro-life cause, anti-alcohol resolutions were one of the few social causes that both sides could agree on. The SBC passed a series of anti-alcohol resolutions in the 1970s, when the denomination was generally under the leadership of the moderates, and a similar series of anti-alcohol resolutions in the early 1980s, when the denomination was under the control of the conservatives.

But not long after conservatives won their fight to take over the SBC, Southern Baptist interest in anti-alcohol campaigns quickly waned. After adopting an anti-alcohol resolution in 1991, the SBC waited fifteen years before considering another resolution on the subject, which was the longest the denomination had ever gone between anti-alcohol resolutions. Then, in 2006, when a resolution on alcohol was brought to the floor for consideration, the resolution sparked more debate than any other SBC resolution discussed that year. It passed with the support of 80 percent of the convention’s messengers, but the debate on the measure signaled that opinion on alcohol was changing among Southern Baptists.

Unlike most previous SBC resolutions on alcohol, the 2006 resolution focused heavily on the question of whether Southern Baptists themselves should consume alcoholic beverages. Previous resolutions had enjoined total abstinence, but almost as an afterthought; the focus instead was on fighting the liquor traffic in the public sphere. But the denomination’s 2006 resolution instead gave primacy to the matter of personal consumption and stated that since “there are some religious leaders who are now advocating the consumption of alcoholic beverages based on a misinterpretation of the doctrine of ‘our freedom in Christ,’” the denomination needed to reaffirm its commitment to total abstinence and urge “that no one be elected to serve as a trustee or member of any entity or committee of the Southern Baptist Convention that is a user of alcoholic beverages.”

Several pastors and other messengers at the convention denounced what they saw as an attempt to legislate what God had not. Jesus turned water into wine, they pointed out. It was not alcohol itself that was the cause of highway deaths, family problems, and numerous other evils, as Southern Baptists had argued for many decades – it was instead the abuse of alcohol.

Conservative Protestants in other denominations – especially conservative Presbyterian denominations – had already been making these arguments for decades. The General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in America, for instance, issued a statement in 1980 opposing mandates for total abstinence from alcohol on the grounds that they would “go beyond the requirements of scripture.” But at the time, those arguments among non-Baptist evangelicals had not deterred Southern Baptists from continuing to pass resolutions reaffirming its absolute opposition to alcoholic beverages. Why then did a significant minority of Southern Baptist pastors start making these arguments in the early twenty-first century when they had not done so in the 1970s or 1980s?

I think that the shift is likely explained by a change in Southern Baptists’ understanding of their own place in the nation’s culture wars.

In the 1970s and early 1980s, the SBC was very much the guardian of southern Protestant culture. Southern Baptists had not yet overcome their longstanding suspicion of Catholics. And most of their Protestant allies from other denominations were from historically anti-alcohol denominational traditions, even if their commitment to the cause of total abstinence was beginning to wane. In the face of cultural moral shifts of which they disapproved, it made sense to many Southern Baptists to double down on all of their traditional moral campaigns – especially their campaign against alcohol. Alcohol, in their view, was still a sign of worldliness and moral laxity; it was not easy to envision it as part of a respectable Christian life.

But by the early 2000s, the situation was very different. As Southern Baptists made abortion and homosexuality their greatest concerns, they began making alliances with Christian groups who had no interest in the temperance cause. Some of their closest allies in the fight against abortion were Catholics, few of whom saw anything wrong with drinking. And in their own seminaries, a growing minority of pastors were adopting an explicitly Reformed theology that made them close allies of conservative evangelical Presbyterians who viewed alcohol as a blessing from God when used responsibly. Even the Reformed Baptists who didn’t drink themselves found it increasingly difficult to embrace an anti-alcohol political campaign that put them at odds with Christians outside their denomination whom they admired. A few decades earlier, the Southern Baptist campaign against alcohol had been an avenue for them to maintain solidarity with other southern Protestant denominations and reaffirm their southern Protestant identity, but by the early twenty-first century, it was increasingly becoming a mark of sectarian oddity.

There were still plenty of Christian groups that eschewed drinking, of course. The majority of Pentecostals and Seventh-Day Adventists (as well as some Wesleyans and members of a few other historically anti-alcohol Christian groups) continued to be teetotalers, but there was no other major Protestant denomination that retained the commitment to the sort of societal vision that had formed the basis for the historic Prohibitionist campaign. The Southern Baptist Convention had retained this vision longer than any other major denomination, but they, too, gave it up when it became apparent that it was sharply at odds with the political and social vision of their Christian allies outside the SBC.

A younger generation of pastors who had never experienced the full fervor of the SBC’s social campaign against alcohol in the name of social uplift – and who instead had equated the SBC’s anti-alcohol stance only with a code of personal behavior that seemed increasingly legalistic and outdated – found it difficult to square the denomination’s opposition to alcohol with Bible verses that described the divinely approved use of wine. Opposition to abortion was easy for them to understand; if the Bible indicated that the fetus was a human being, then abortion was murder, and it needed to be opposed in the political sphere. And opposition to drunkenness (which the Bible clearly condemned) was also equally understandable. But if alcohol itself was intrinsically a morally neutral substance when used in moderation, why was it the church’s business to fight a public campaign against alcohol only because it had the propensity to be abused?

An earlier generation of Protestants had argued in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that alcohol was inherently addictive and unsafe, and the Southern Baptists of the 1970s and 1980s retained a version of this argument by arguing that even if alcohol was not necessarily addictive for everyone, it caused enough harm among enough people to justify staying away from it entirely. The safest way to avoid becoming an alcoholic, they said, was to avoid taking the first drink.

But some conservative Presbyterians argued that alcohol abuse was a symptom of a spiritual problem, not the direct result of some addictive quality within alcohol itself. Alcohol, in other words, was less like heroin and more like money – that is, something that could certainly be abused or become addictive through the user’s own sin, but that in itself was a gift from God to be enjoyed for his glory. And if that was the case, fighting against alcohol in the public sphere made no sense at all. Nor did restricting its use among Christians.

Historically, Protestant opposition to alcohol stemmed from two main theological streams: a holiness stream that was concerned about personal behavior and a Social Gospel stream that wanted to improve society. Wesleyan groups abstained from alcohol even in the early nineteenth century because of their concern for holiness – and even in the twenty-first century, when the United Methodist Church has abandoned its total abstinence stand, a number of smaller Wesleyan groups, as well as many Wesleyan-influenced Pentecostals, have retained their commitment to teetotalism on personal holiness grounds. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, members of other Protestant denominations that were never part of the holiness stream – such as Congregationalists, Disciples of Christ, and Presbyterians – supported the temperance and Prohibitionist campaigns because of their belief that the saloon in particular – and alcohol use in general – were detrimental to society and needed to be eradicated.

Baptists were not firmly in either the holiness or the Social Gospel streams, which is why they were not early leaders in the temperance movement. Instead, more than anything, they were influenced by a theology of personal conversion. In and of itself, that theology did not have to mandate teetotalism. But in the late nineteenth century, Baptists were sufficiently influenced by both a concern for personal holiness and a commitment to Protestant-inspired societal moral uplift to find the temperance movement attractive – and because this commitment solidified their status as guardians of southern Protestant morality, they remained in the temperance movement longer than most other Christians did.

But by the twenty-first century, neither the holiness nor the Social Gospel streams of Protestant theology had much influence on a younger generation of Southern Baptists, especially for those who self-identified as Reformed. To some of them, the denomination’s longstanding commitment to the campaign against alcohol seemed anachronistic and misguided.

Southern Baptists were thus silent this year about the new research findings showing the health dangers of alcohol. A half-century ago, they would have been delighted to welcome this evidence as proof that alcohol was just as dangerous as they had claimed, but now it doesn’t fit very well with their current theology, so they saw no need to comment on it.

That doesn’t mean that most Southern Baptists are now drinking. A 2007 LifeWay survey indicated that only 3 percent of Southern Baptist pastors (and 29 percent of lay Southern Baptists) drank alcohol. Eleven years later, in 2018, another LifeWay survey showed that 33 percent of Baptists drank alcohol – the report did not differentiate between clergy and laity this time – but that still meant that the majority claimed to be teetotalers. County maps of per capita alcohol sales support this conclusion; counties in the Baptist-dominated southern Bible belt have some of the lowest alcohol consumption rates in the country, second only to heavily Mormon Utah.

But even if most Southern Baptists are refraining from drinking, they’re much less likely than they used to be to tell others that they shouldn’t – and that’s a significant shift for the denomination. So far, the shift hasn’t received much scholarly analysis. But for those who care about the study of religion, politics, and social mores, this shift can tell us a lot about significant cultural and political trendlines. After all, when the nation’s largest historically teetotaling denomination shows no interest in commenting on a surgeon general’s warnings against alcohol, its silence speaks volumes.