As I was writing the review of Nigel de S. Cameron’s Dr. Koop that Christianity Today published this week, I realized that the spiritual and political journey of Dr. C. Everett Koop (President Ronald Reagan’s surgeon general) tells us a lot about the trajectory of modern evangelicalism and the centrist Protestants who didn’t quite fit into the culture-war agenda.

Koop was one of those centrist Protestants. Because of his strong public opposition to abortion, many pro-life Christian conservatives in the early 1980s were excited when he became surgeon general, and they were his strongest supporters at his polarizing confirmation hearings. But to the surprise of almost everyone – including both supporters and critics – Koop gave almost no attention to the abortion issue during his time as surgeon general. Instead, while continuing to oppose abortion, he became critical of the pro-life movement’s culture war politics and focused on other issues that he thought could save lives – especially public health campaigns to discourage smoking and encourage condom use to prevent the spread of HIV / AIDS.

As I point out in the review, conservative evangelicals misunderstood Koop because they thought of opposition to abortion in culture war terms – and Koop was not a culture warrior. Although he was strongly convinced that abortion killed innocent human lives and that human life should be valued and preserved from the moment of conception, he opposed antiabortion laws, because he believed that the pro-life campaign should rely on public persuasion rather than legal coercion to save lives.

This was actually not an usual stance in the late 1970s and early 1980s. While most of the conservative evangelicals who entered the pro-life movement at the time thought of the campaign against abortion primarily in political terms, some smaller groups of pro-life Protestants did not. In 1980, the same year in which the Southern Baptist Convention passed an antiabortion resolution that was strongly political (calling as it did for restrictive abortion policies and an antiabortion constitutional amendment), the General Conference Mennonite Church passed a resolution on abortion that quoted from Psalm 139 and affirmed the high value of the fetus, but also declared, in true Anabaptist fashion, “We believe that the demands of discipleship are to be accepted voluntarily, not imposed legally upon everyone regardless of conviction. . . . We believe, however, that the church should witness to society concerning the sanctity of the fetus. We also believe that the church should be concerned that legislation not coerce people to act against their convictions and that it conform to standards of justice.”

Koop was not an Anabaptist, but based on the information that Cameron presents in his biography, it seems that he would have agreed far more with the General Conference Mennonite Church’s resolution than with the Southern Baptist Convention’s, which included several statements about abortion policy and that concluded with the line, “We favor appropriate legislation and/or a constitutional amendment prohibiting abortion except to save the life of the mother.”

What Koop actually was, I think, was a moderately conservative mainline Protestant with an evangelical view of salvation, but with a strong aversion to both fundamentalism and culture-war politics. In the mid-to-late 20th century, there were a lot of Christians like Koop, and for a long time, they felt relatively comfortable occupying the conservative wing of mainline Protestant denominations.

As I discovered in my archival research for my forthcoming book Abortion and America’s Churches (which will be released from the University of Notre Dame Press on October 1), every mainline Protestant denomination in the 1980s and 1990s – including the Presbyterian Church (USA), the United Church of Christ, and the United Methodist Church, among others – had a pro-life minority that usually identified as evangelical and that held at least moderately conservative theological beliefs about biblical authority and salvation. But in contrast to Southern Baptists, most of those mainline Protestant pro-life Christians (which, in the 1990s, included theologians such as Richard Hays and Stanley Hauerwas) were reluctant to endorse antiabortion laws and other conservative culture-war causes. They opposed same-sex marriage and sex outside of marriage, but they did not get behind the political efforts to fight gay rights in the public square.

For much of the mid-to-late 20th century, those generally traditionalist, theologically conservative, politically centrist mainline Protestants felt welcome in an evangelical movement that was dominated by other northern Protestants with connections to the mainline – that is, people like Christianity Today editor Carl F. H. Henry, who was one of Koop’s friends. Like Koop, Henry had grown up in New York City, and like Koop, he identified for much of his life with the evangelical wing of a northern mainline denomination – in Henry’s case, the American Baptist Convention, and in Koop’s case, the United Presbyterian Church (now the PCUSA).

Koop moved in northern evangelical circles for most of his adult life, speaking at Wheaton College and collaborating with Francis Schaeffer on a pro-life documentary and book. But he was never entirely comfortable with all aspects of American evangelicalism. In the 1950s, when conservative evangelical culture was still characterized by a set of behavioral codes that included abstinence from alcohol, he generally rejected those fundamentalist proscriptions and continued to drink martinis.

But since northern evangelicalism at the time was still defined above all by a commitment to biblical inerrancy, any Protestant who accepted biblical authority and who had a personal relationship with God through faith in Jesus and in his substitutionary death on a cross could still fit into the broadly-based evangelical movement. Koop might not have been able to accept every tenet of faith and behavior that would have been required for faculty at Wheaton College in the mid-20th century, but he was still invited to give public lectures there. He was still, in other words, welcomed as an evangelical.

But Koop’s relationship with evangelicalism became increasingly strained after the 1980s, when evangelicalism increasingly became identified with a form of culture-war politics that Koop eschewed. As I have argued elsewhere, the Christian Right of the late 20th century was largely the creation of Sunbelt evangelicalism, a form of evangelicalism that was alien to Koop and to other northern conservative mainline Protestants like him. Koop was unfamiliar with the Sunbelt and its values. He spent his entire life in the Northeast corridor; he was born in New York City, he spent most of his professional career in Philadelphia, and after working briefly in Washington, DC, he retired to Vermont. He was never a Baptist, let alone a Southern one.

He was also never a Christian Right Republican, even though he worked for the Reagan administration. In his private life, he was nonpartisan, but he was more friendly to Democrats than Republicans in his later years. In the 1990s, he publicly campaigned for Bill Clinton’s healthcare plan, and to the end of his life, he considered himself a friend of Hillary Clinton – largely because he believed that a universal health insurance plan would save lives.

Koop seemed to recognize at the time that he was probably more comfortable with the conservative end of northern mainline Reformed Protestantism than with a southern-based evangelicalism. When his church (Tenth Presbyterian in Philadelphia) voted to leave their mainline Presbyterian denomination and join the evangelical Presbyterian Church in America in 1982, Koop opposed the move. In his later years, he attended the evangelical (and Reformed) Congregationalist church in Vermont where his son was a pastor – which may have been one of the relatively few remaining outlets for someone who was theologically conservative and Reformed, but not a culture-war conservative or a Southern Baptist-style evangelical.

The minority wing of evangelicalism that Koop was a part of is smaller today than it was a generation ago, during Koop’s life. If Koop was uncomfortable with the culture-war trends in evangelicalism in the late 20th century, it’s hard to imagine that he would be any more comfortable with those trends today, if he were still alive. For someone who was a strong believer in science and who was a close friend of Anthony Fauci (who was both his colleague and his personal physician), it’s hard to imagine that he would have endorsed the evangelicals who protested against mask mandates or vaccines during COVID. For someone who endorsed universal healthcare, it’s hard to imagine that he would have found much in common with the contemporary Republican Party.

But I’m not sure if Koop would feel very comfortable with mainline Protestantism either. His strongly Reformed view of God’s sovereignty, his belief in the literal historicity of the gospels, and his aversion to culture wars of any type (whether on the right or the left) might have put him at odds with a contemporary mainline that has lost most of its once-vibrant evangelical minority. Perhaps that’s one reason why Koop didn’t affiliate with mainline Protestantism in his old age – and why, if he had lived longer, he might have felt very uncomfortable with its leftward turn.

Koop’s outspokenness abortion would certainly be at odds with mainline Protestant denominations such as the PCUSA that endorse abortion rights as a matter of social justice. In Koop’s own day, mainline Protestant denominations officially opposed antiabortion legislation, but expressed concerns about its morality, but today, those concerns are almost entirely gone from mainline Protestant resolutions on the subject and have been replaced by political lobbying for “reproductive justice.”

But if Koop’s own preferred northern-centered, politically centrist, theologically conservative Protestantism is smaller and less visible than it was in his own life, I don’t think that it has entirely disappeared.

Where would someone like Koop find a church home today? I suspect that on the local level, someone with Koop’s theology and political views might find a few kindred spirits in a northern ECO Presbyterian church, some urban Christian Reformed Church (CRC) congregations, and possibly even a multicultural, politically irenic, evangelical Presbyterian congregation such as Redeemer Presbyterian Church in New York. For those who are not Reformed, there are a few other denominations – like the North American Lutheran Church, the Evangelical Covenant Church, or some congregations in the American Baptist Churches USA – that may also straddle the contemporary divide between evangelicalism and liberal Protestantism by holding onto historic Christian truth claims while largely bypassing many of the contemporary evangelical culture wars.

But at the national level, centrist Protestantism of the sort I have described has very little influence. Most of the denominations that might fit most closely with centrist Protestantism have fewer than 1 million members – which means that they are less than 10 percent of the size of the Southern Baptist Convention. As the number of mainline Protestants has declined, so has the number of centrist Protestants. And many of those that remain are not a comfortable fit for either side in America’s two-party political system or its culturally polarized religious scene.

As a result, those who identify with some form of centrist Protestantism may feel at odds with the prevailing trends in both politics and theology. What was once a vibrant tradition has been almost completely cut off from the national conversation.

But for the sake of both our national politics and our national religious life, we need the wisdom of centrist Protestants who know how to hold onto important theological truths without attaching the faith to contemporary partisan political divisions. In the past, centrist Protestants like Koop have been important members of the evangelical coalition – and maybe a few of them can still be again.

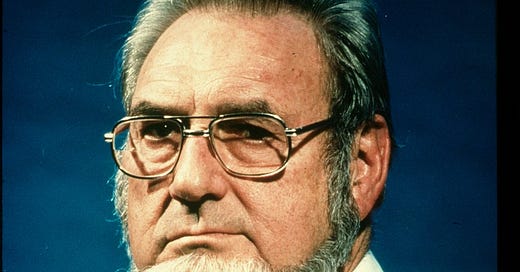

(Photo: C. Everett Koop; Photo by Ernie Branson / National Institutes of Health)

Excellent piece and excellent reminder of how artificial the theological and political fault lines of American Christianity (and particularly evangelicalism) really are. Although he was active before my time, I first read about Koop in Phillip Yancey’s book Soul Survivor as one of the “unlikely mentors” who saved my faith from being destroyed by the church, and I resonate with both his theological convictions and his reticence about hitching those convictions to a particular political platform.

History has proven his reticence well-founded. If theological convictions are subordinated to a political platform, then those with no convictions can easily hijack that platform and co-opt its supporters to their own ends.

Nice reminder of that centrist evangelicalism that I've valued over my adult life. It was not difficult to find these friendly estuaries within West Coast PCUSA churches until more recently. And I recall Koop serving as an usher at 10th Pres, Phil, in 1973-74 when I occasionally attended there (James Boice was pastor). I shouldn't speak for others, but why not: I think Koop represented the sort of evangelical whom we easily identified with over my 30+years (1986-2017) with InterVarsity Press.